A Modern Way to Live: our co-founder Matt Gibberd on materials

When it was first published in 2021, we ran some excerpts from our co-founder Matt Gibberd’s book, A Modern Way to Live, which looked at the five principles that best-designed homes tend to pay attention to and which make for happier, healthier living environments: space, light, materials, nature and decoration. That we should return to them periodically makes sense, which is why, this year, we’ve been theming our stories month by month. With the first two behind us, the arrival of March means it’s time to talk materials. But before you start dreaming of all the stories we’ve lined up (trust us, they’re good), we’re returning to Matt’s book and to his thoughts on the subject.

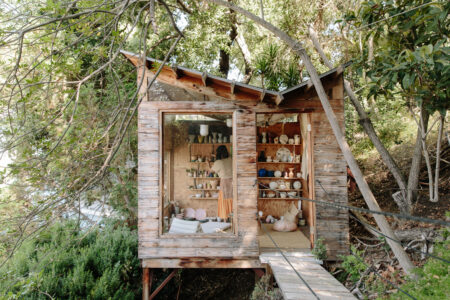

When I was growing up, we often spent our summer holidays at a converted sailing school on the Norfolk Broads; a timber shack raised above the water on stilts, with the upturned hull of a rowing boat as its front door. The walls were lined with faded photographs of gurning fishermen proudly parading their pike. I still remember the smells vividly: ground bait and maggots in tackle boxes, damp dogs, musty beds and Samson rolling tobacco. Most of all, though, it’s the house’s materiality that sticks in the mind: the feeling of woollen blankets clasped against the skin, of bare feet on wooden floors, and of elbows against the smooth oilcloth that covered the dining table, where we played Dingbats and Nomination Whist after the sun went down.

The tactility of a place is one of its most defining characteristics. We have friends in France who I always look forward to staying with, not just because of their excellent company, but also because their house has outrageously plump sofas and the softest Egyptian cotton bedsheets. My wife, Faye, and I aspire to this level of comfort, but, historically at least, have struggled to achieve it. In our previous house, the kitchen units were made from aluminium sprayed with car paint, which looked great but were a bit, erm, clangy. My favourite Marcel Breuer chair wasn’t terribly ergonomic, especially because its left arm kept falling off. And our bed was one of those bow-shaped ones where you both end up in a tangle in the middle.

Touch is perhaps the most underestimated of the human senses. Helen Keller, who could neither see nor hear, poignantly described her reliance on haptic discovery in The World I Live In: “I have just touched my dog. He was rolling on the grass, with pleasure in every muscle and limb. I wanted to catch a picture of him in my fingers, and I touched him as lightly as I would cobwebs; but lo, his fat body revolved, stiffened and solidified into an upright position, and his tongue gave my hand a lick! He pressed close to me, as if he were fain to crowd himself into my hand. He loved it with his tail, with his paw, with his tongue. If he could speak, I believe he would say with me that paradise is attained by touch; for in touch is all love and intelligence.”

Choosing a certain material for the home is a juggling act of conflicting considerations: does it look good, how sustainable is it, how long will it last, what is the cost, and so on. Arguably the most important question of all is: how does it feel? Much as Helen Keller did, we could all learn a little from our canine companions, who naturally seek out the most comfortable places, stretching out in front of the fire or settling themselves onto the sofa with a satisfied sigh.

You don’t have to spend a huge amount of money to achieve a richer and more tactile interior. When Faye and I once rented a cottage for 18 months between house moves, we purged the walls of their yellowness using a pot of natural white paint, switched out the chrome-effect plastic knobs on the cupboards for black metal ones, and hung some simple linen curtains at the windows. The place became completely unrecognisable. When our tenancy came to an end, the cottage rented again straight away with no void period, so the landlord was happy, too.

In any home from any era, we should ask ourselves how it wants to be and acknowledge the original design intent. Retaining as much as possible of the existing building fabric makes sense from a environmental perspective, and reinstating natural materials that have been lost over the years helps re-establish the house’s identity. There are also clear health benefits to using natural rather than made-made materials. For example, untreated wood like cedar is non-toxic and naturally resistant to rot and pests, and can be used for anything from cladding to decking and interior joinery. Clay is a seldom-used alternative to conventional gypsum plaster; not only does it absorb smells, it is also hygroscopic, helping to maintain an optimal humidity level and preventing the growth of mould and fungi.

Copper is something of a wonder material. The Smith Papyrus, an Egyptian medical text, describes how it was used to sterilise drinking water and wounds, and the Romans, Greeks and Aztecs all adopted it for its hygienic attributes, treating everything from headaches to ear infections. Medical interest was heightened during the 19th century, when it was observed that copper workers seemed to be immune to cholera. More pertinently for modern use, the coronavirus can survive for days on a stainless steel or glass surface, yet dies within hours of landing on copper.

A few years ago, I visited the architect Duncan McLeod and his wife, Lyndsay Milne McLeod, at their wonderful family house in north-west London. The couple talked about how they chose to retain the original wooden floorboards, with their natural gouges and blemishes, because they felt they would cause less anxiety than a new floor made from something shiny. Indeed, most of us can remember living in a place with a kitchen floor that shows up every dusty footstep and errant breadcrumb.

In my view, we should let go of the idea that everything must be immaculate and unblemished. The Japanese have always embraced the notion of flawed beauty in a way that we in the West have never managed. Wabi-sabi teaches us to accept transience and asymmetry, find joy in weathered surfaces and mismatched materials, and accept what you have rather than fighting against it. As the great Swiss architect Peter Zumthor once declared: “A good building must be capable of absorbing the traces of human life and taking on a specific richness . . . I think of the patina of age on materials, of innumerable small scratches on surfaces.”